Written by Judith Haydel, published on August 3, 2023 , last updated on February 18, 2024

Privacy generally refers to an individual’s right to seclusion, or right to be free from public interference. Often privacy claims clash with First Amendment rights. For example, individuals may assert a privacy right to be “let alone” when the press reports on their private life or follows them around in an intrusive manner on public and private property. There is no explicit mention of privacy in the U.S. Constitution, but in his dissent in Gilbert v. Minnesota (1920), Justice Louis D. Brandeis, pictured here, nonetheless stated that the First Amendment protected the privacy of the home. In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), Justice William O. Douglas placed a right to privacy in a “penumbra” cast by the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments. (Image via Library of Congress, circa 1916, public domain)

Privacy generally refers to an individual’s right to seclusion, or right to be free from public interference. Often privacy claims clash with First Amendment rights. For example, individuals may assert a privacy right to be “let alone” when the press reports on their private life or follows them around in an intrusive manner on public and private property.

Right to privacy found in the Constitution

Much like liberty, justice, and democracy, privacy appears to be an easy concept to understand in the abstract. Defining it in a legal context, however, is difficult and complicated by the fact that there are constitutional rights to privacy and also common law or statutory rights of privacy.

There is no explicit mention of privacy in the U.S. Constitution, but in his dissent inGilbert v. Minnesota(1920),Justice Louis D. Brandeisnonetheless stated that the First Amendment protected the privacy of the home. InGriswold v. Connecticut(1965),Justice William O. Douglasplaced a right to privacy in a “penumbra” cast by the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments.

Right to privacy found in common law

Initially, the common law upon which the U.S. Constitution, state constitutions, and state laws are based, protected only property rights. During the 1880s, however, legal scholars began to theorize that the common law of torts, which involves injuries to private persons or property, also protected against government invasion of privacy.

In the late 1880s, Judge Thomas Cooley wrote inA Treatise on the Law of Torts or the Wrongs Which Arise Independent of Contractthat people had a right to be let alone. Boston lawyers and former Harvard Law School classmates Samuel D.Warren and Louis D. Brandeis elaborated on this concept in their seminal 1890 article in the Harvard Law Review, “The Right to Privacy.” They argued that the common law’s protection of property rights was moving toward the recognition of a right to be let alone. Their article inspired some state courts to begin interpreting the civil law of torts to protect a right of privacy.

Types of privacy claims

Later, Dean William Prosser, a torts law expert, in an influential 1960 article in the California Law Review wrote that there are four distinct types of privacy torts:

- intrusion upon solitude,

- public disclosure of private facts,

- appropriation of another’s name or image,

- and publishing information that puts a person in afalse light.

Sometimes privacy tort claims conflict with First Amendment free speech or free press claims. For example, the press may publish sensitive details of a person’s private life and be charged with a public disclosure of private facts tort.

There are four types of privacy claims, including intrusion on seclusion through surveillance like wiretapping.This telephone de-bugging meter discovers any transmitter (bug) in the phone or in the lines leading to it. De-bugging devices are bought mostly by business executive who suspect espionage by competitors. (AP Photo/Robert Kradin, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Supreme Court has decided First Amendment privacy cases

The Court has rendered a number of decisions involving First Amendment freedoms and privacy. InPacker Corporation v. Utah(1932), Justice Brandeis suggested that the Court should consider the conditions under which privacy interests are intruded upon. His suggestion foreshadowed the Court’s later development of the distinction between privacy interests in the home and in public.

The First Amendment protection of privacy is greatest when the invasion of privacy occurs in the home or in other places where an individual has a reasonable expectation of privacy. For example, despite the fact thatobscenityis not protected by the First Amendment, inStanley v. Georgia(1969)the Court struck down a Georgia law prohibiting the possession of obscene materials in the home.Justice Thurgood Marshallwrote: “If the First Amendment means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch. Our whole constitutional heritage rebels at the thought of giving government the power to control men’s minds.”

InFederal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation(1978), the Court upheld aFederal Communications Commissionban onindecent speechon the radio, because radio broadcasts invade the privacy of the home, it is difficult to avoid them, and children have access to them.

Little First Amendment protection of privacy in public

In public, on the other hand, there is little or no First Amendment protection of privacy. InCohen v. California(1971), the Court held that the privacy concerns of individuals in a public place were outweighed by the First Amendment’s protection of speech, even when the speech includedprofanityin a political statement written on a man’s jacket.

Freedom of association is strongest First Amendment protection for privacy

Court decisions involving privacy rights are sometimes based on more than one First Amendment provision, and it can be difficult to differentiate privacy cases on the basis of a specific First Amendment right. In general, the strongest First Amendment protection for privacy is in the right of freedom of assembly and, by judicial interpretation,freedom of association. That protection, however, is not absolute: organizations whose goals are unlawful are not protected.

InDe Jonge v. Oregon(1937), the Court declared that the right of people peaceably to assemble does not extend to associations that incite violence or crime. The Court inNAACP v. Alabama(1958)ruled that freedom of assembly includes the right to freedom of association and acknowledged that individuals are free to associate for the collective advocacy of ideas. Compelled disclosure of the NAACP’smembership lists, which was at issue in the case, would in effect suppress the Association’s ability to do business and hinder the group’s members from expressing their views.

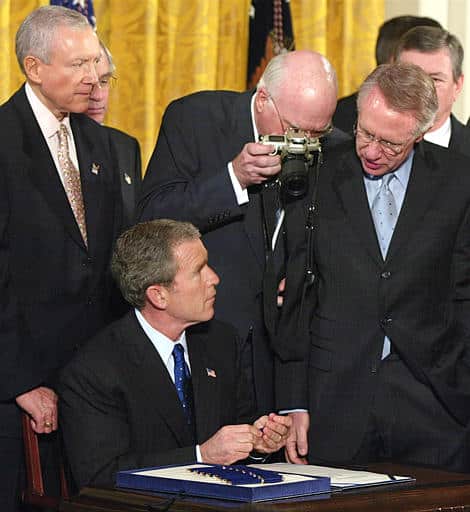

Advances in technology, including the ubiquity of the Internet, are far outpacing government’s ability to address privacy issues in these new and ever-changing contexts. To make matters even more complex, national security interests are now entangled in this web of technological sophistication. National security concerns in the wake of the September 11, 2001, destruction of the World Trade Center led to passage of the USA Patriot Act. Parts of the act expand government power to conduct surveillance of Americans. Although it prohibits investigations of Americans’ activities that are protected by the First Amendment, some government actions have been challenged in the courts as violating First Amendment rights. In this photo, Sen Patrick Leahy D-Vt. peers over the shoulder with his camera as President Bush signs the Patriot Act Bill during a ceremony in the White House East Room, Friday, Oct. 26, 2001. (AP Photo/Doug Mills, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Privacy rights usually take back seat to media rights

Although the press does not have additional First Amendment rights that the public does not also enjoy, privacy rights ordinarily take a back seat to the media’s right to gather and publish truthful information that is available in public documents. For example, inCox Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn(1975)the Court ruled that freedom of the press interests in publishing publicly available information about the commission of a crime outweighed privacy rights. And inBartnicki v. Vopper(2001), the Court upheld the right of a radio station to broadcast a private telephone conversation involving public persons and concerning political matters that was illegally intercepted by an anonymous third party.

Technology advances and national security interests are making privacy rights more complex

Advances in technology, including the ubiquity of the Internet, are far outpacing government’s ability to address privacy issues in these new and ever-changing contexts. To make matters even more complex, national security interests are now entangled in this web of technological sophistication.

National security concerns in the wake of the September 11, 2001, destruction of the World Trade Center led to passage of theUSA Patriot Act. Parts of the act expand government power to conduct surveillance of Americans. Although it prohibits investigations of Americans’ activities that are protected by the First Amendment, some government actions have been challenged in the courts as violating First Amendment rights. Early cases involved the National Security Agency’swiretapping practicesand agag orderprovision that prevented recipients of national security letters from revealing they had received such a letter. It will take future litigation to determine the proper balance between privacy and national security.

This article was originally published in 2009.Dr. Judith Ann Haydel(1945-2007) was a political science professor at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette and McNeese State University.